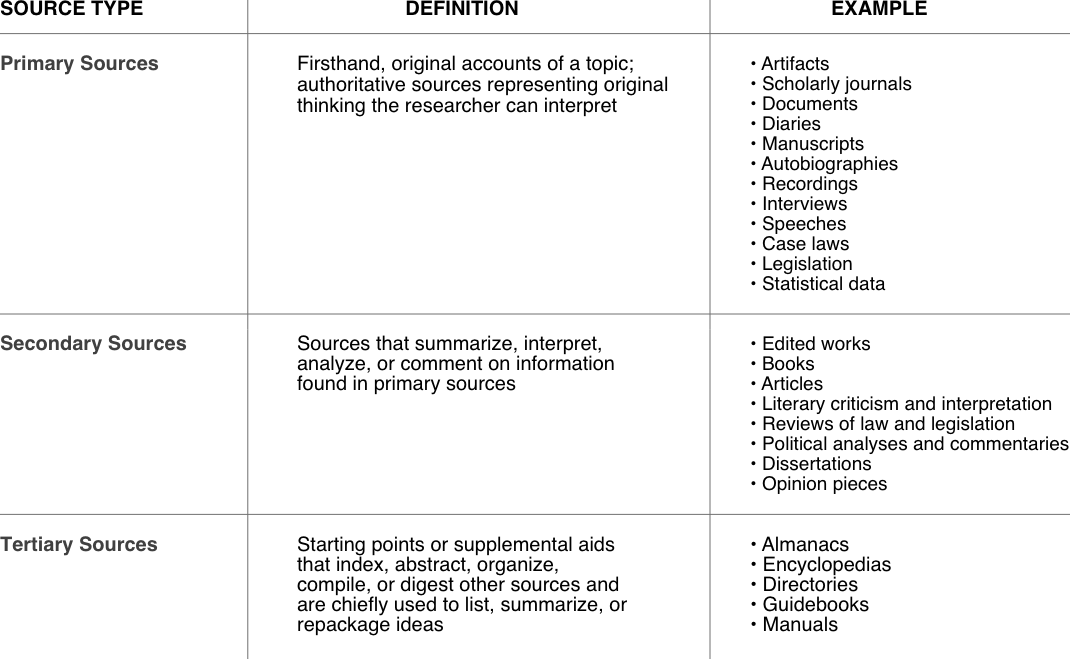

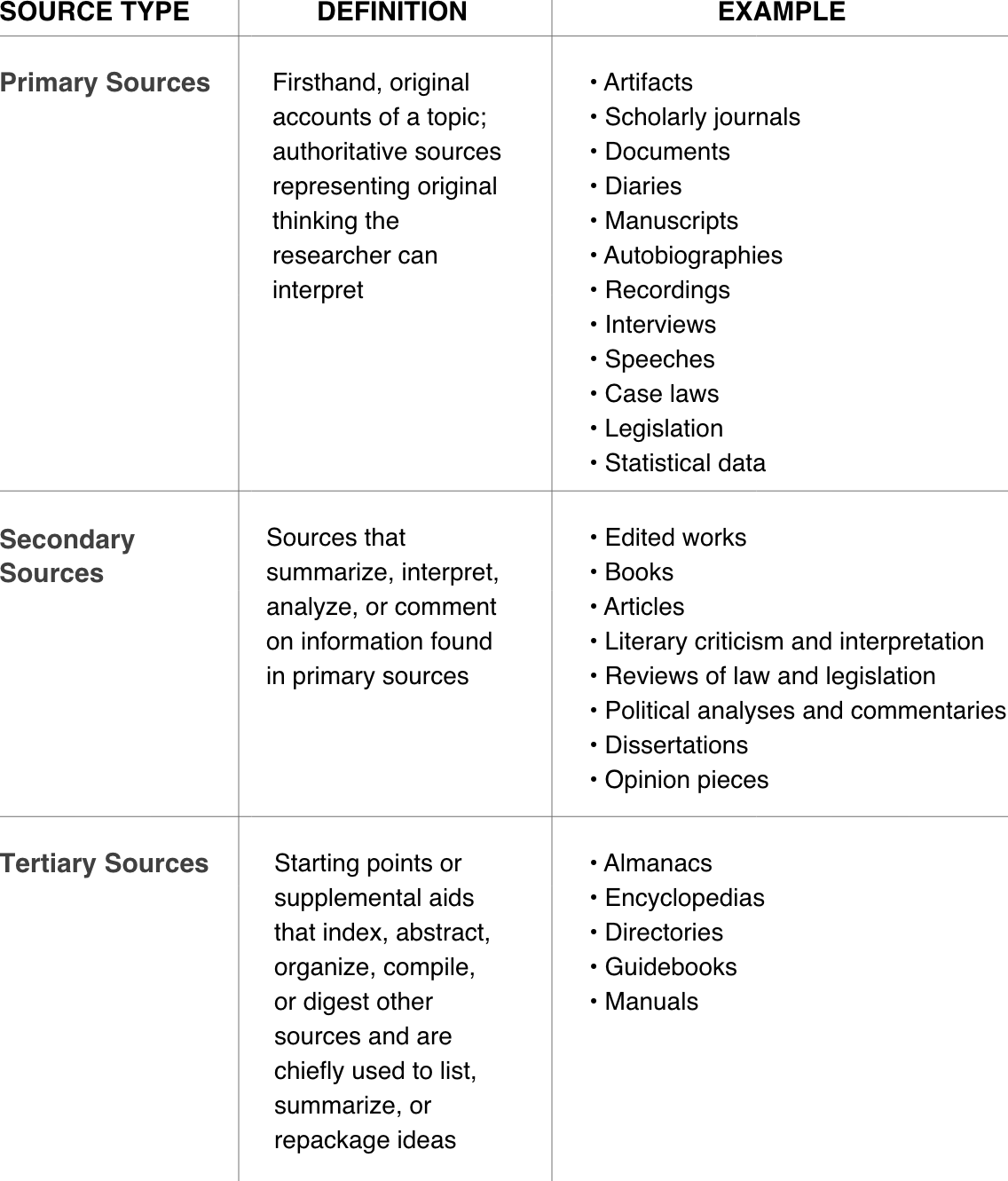

Source Type | Definition | Example |

|---|---|---|

Primary Sources | Firsthand, original accounts of a topic; authoritative sources representing original thinking the researcher can interpret | •Artifacts •Scholarly journals •Documents •Diaries •Manuscripts •Autobiographies •Recordings •Interviews •Speeches •Case laws •Legislation •Statistical data |

Secondary Sources | Sources that summarize, interpret, analyze, or comment on information found in primary sources | •Edited works •Books •Articles •Literary criticism and interpretation •Reviews of law and legislation •Political analyses and commentaries •Dissertations •Opinion pieces |

Tertiary Sources

| Starting points or supplemental aids that index, abstract, organize, compile, or digest other sources and are chiefly used to list, summarize, or repackage ideas | •Almanacs •Encyclopedias •Directories •Guidebooks •Manuals |

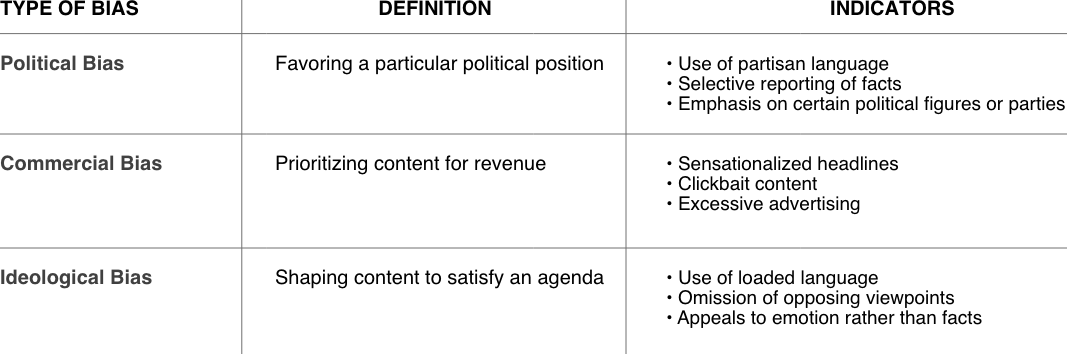

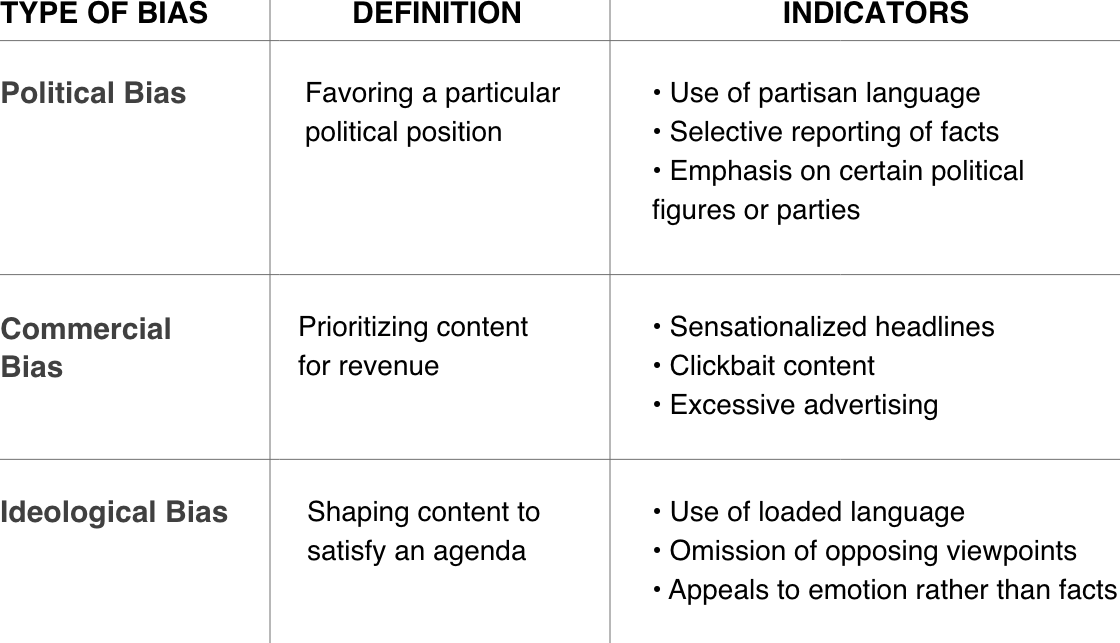

Type of Bias | Definition | Indicators |

|---|---|---|

Political Bias | Favoring a particular political position | •Use of partisan language •Selective reporting of facts •Emphasis on certain political figures or parties |

Commercial Bias | Prioritizing content for revenue | •Sensationalized headlines •Clickbait content •Excessive advertising |

Ideological Bias | Shaping content to satisfy an agenda | •Use of loaded language •Omission of opposing viewpoints •Appeals to emotion rather than facts |

When it comes to AI, teachers deserve actionable guidance that strengthens instructional decision-making. Download our 5 Plays for AI-Powered Planning playbook for five practical ways to use AI as a planning partner.

Level-up current events into dynamic learning!